How Lists Help Autistics Function

We all understand how difficult it is to have 20 tasks to accomplish and not very much time. Or we have 10 things we want to do and have to prioritize them so that we don’t get into trouble with people we have promised things to, or our families, or meeting deadlines at school or work.

Autistics often have trouble keeping more than one thing in mind at a time. This is either because our brains just cannot visualize a list and keep it at the forefront of our thoughts or because our brains follow rabbit trails constantly and mental notes end up falling in holes along the way. Many adult autistics grew up being punished for unfinished chores or not completing the list of things told to us in the morning--while some of us were gifted with amazing memories during childhood, most of us needed to adapt by making lists.

Autistics really do not like to disappoint others, so failing to do a task eats away at our self-esteem. The biggest way we can help our students increase their confidence and self-esteem is to let them know that making lists is a way to help themselves.

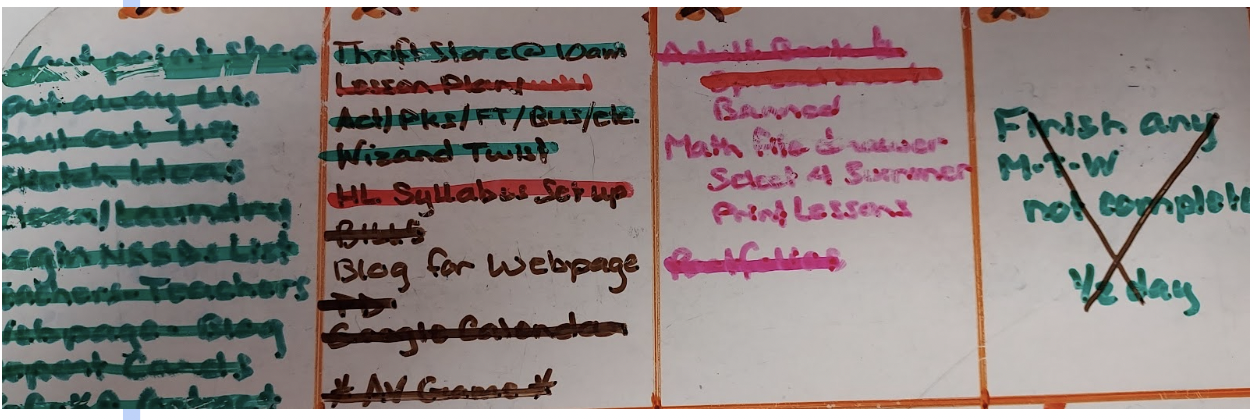

If your child has some homework, chores, or other projects that need to be done, help them make a list. Whiteboards are great for this because erasing things off the list can be so satisfying. Checklists help you see what you have done and prove to others that you are accomplishing things. Using their planners is another option because it can help organize and keep all those lists in one place.

How do you do this?

Write down everything that needs to be done. Help your child prioritize what needs to be done (is there a deadline, like getting the trash out before the truck drives by?) and then help them write a checklist in the order they have chosen.

After a week or so of doing this with them every day, let them try on their own and share what they have done. They you can discuss what they missed, praise how they figured things out, and let them learn by doing.

Personally, I had an amazing memory as a child (I still have an almost eidetic memory concerning conversations) but traumas, age, and other events have caused that memory to erode. I struggled for many years feeling like I was adrift and lost. Then I discovered that when I make a list I have improved my memory because I can visualize the list I wrote. Sometimes I can move my hand to remember the words I wrote. Mostly I can carry the list with me to make sure I don’t forget something. The added bonus is that being able to cross things off my list is so satisfying that it inspires me to keep working on it.

For my youngest daughter, those big assignments at school would throw her into a meltdown. The immensity of the project was too much, and because it all seemed like too much, she did nothing until the night before when her meltdown would reach epic proportions and I would have to work with them for 6-8 hours before starting my next 14 hour day at work. This did not work for me. So one day, I pushed a few extra buttons as she came out of her meltdown and made her admit that she needed help organizing larger projects. I made her write it on our whiteboard while she was still sobbing so that when she was calmer we could talk and plan…her own words being proof that this was what she really wanted.

I had to have it in her own words because she does not like me telling her what to do, asking too many questions, and intruding into her life. Her words on the whiteboard were there for me to point to every time I got home and began to inquire about her day. Her words stopped her meltdowns because she would remember why she wrote them and that I was only trying to help her.

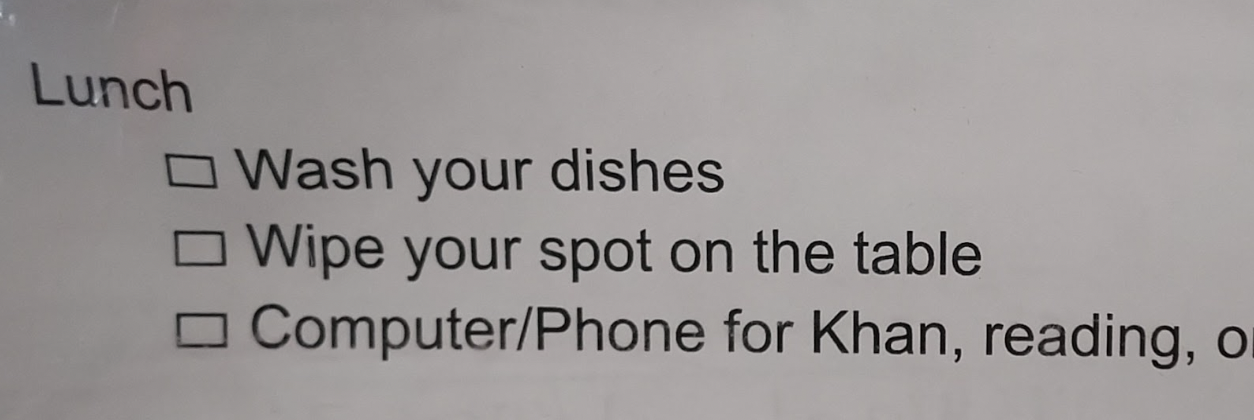

Every day I would ask what her homework was until we got a big project. Then we sat down and broke it apart into smaller pieces. I bought her a whiteboard for her bedroom door and we wrote each day’s list onto the board. We included the reward breaks, that were timed, for each part of the project she got finished. It would look a bit like this:

- brainstorm ideas for paper, come up with at least 5 (her choice of how many)

- 10min break playing Paper Mario (She chose what each break would be because she said that was also a hard choice for her to make)

- Look at your ideas. Which one (or two) do you think would work best? Brainstorm ideas to write about.

- 20 min break working on the line drawing of your commission

- Go on a walk with the dog

- Do 20 minutes of assigned reading

Each evening when I got home we would go over what she had done. I would help her with trouble areas of her project, and we would analyze if that schedule worked. Then we would make the next day's schedule with needed adjustments. After about a semester of us doing this together every day, she stopped asking for help and never had a big project meltdown, or a procrastinated paper again.

In her sophomore year in college she began researching different types of scheduling and experimenting with a different one each couple of weeks to see what worked best for her. I was so proud of her!